- Home

- Maggie Groff

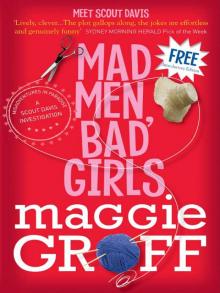

Mad Men, Bad Girls

Mad Men, Bad Girls Read online

Meet Scout Davis.

Investigative journalist. Tea enthusiast. Guerilla Knitter.

When an American cult moves to the Gold Coast, Scout’s investigative antennae start quivering. She sets out to expose the cult’s bizarre practices, but when she learns the identity of a recent recruit, her quest becomes personal. And dangerous.

Meanwhile, her sister Harper, Head of Sport at a posh school, needs a favour regarding a strange case of vandalism.

But Scout has her own secret. In the dead of night she sneaks out with the Guerilla Knitters Institute, an underground group of yarn bombers, to decorate Byron Bay with radical artworks. Scout suspects that the local police sergeant, Rafe Kelly, is hot on her tail. And she doesn’t mind that one bit . . .

Contents

Cover

Blurb

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Chapter 56

Chapter 57

Chapter 58

Chapter 59

Chapter 60

Chapter 61

Acknowledgements

Good News, Bad News sneak peak

About Maggie Groff

Copyright page

For Hannah Kay

Follow your dreams, darling girl

Chapter 1

It was a hot March morning in Byron Bay. My partner Toby was in Afghanistan, on assignment for Reuters, so I had the apartment to myself. Well, almost. Chairman Meow, my grey smooth-haired cat, was curled up on the old Windsor chair beside my desk. He was supposed to be sending me inspirational vibes, but his mind wasn’t on the job today—so far I’d only intercepted snoring.

I was checking final edits on an article I’d written for Newsweek when the home phone rang. It was Brian Dunfey, a commissioning editor at Anzasia Media Group. I’m a freelance investigative journalist and Brian has been sending work my way for more years than either of us care to remember.

‘Have you ever heard of a cult called the Luminous Renaissance of Illustrious Light?’ Brian fired down the line, and I wondered, not for the first time, if he’d learned his telephone etiquette from the court martial chapter in an army training manual.

‘I’m very well. How are you?’ I greeted him.

‘Yeah, yeah, everyone’s a smart-arse.’

I laughed. ‘Good to hear from you, Brian. And, no, never heard of them. Are they here in Byron?’

‘No room, the place is already full of industrial-grade lunatics.’

Brian has no time for what he considers the hedonistic, self-indulgent behaviour and anti-establishment ways of my hometown. I’ve heard him refer to Byron Bay as the land where the bong tree grows. Once, he put Bonking Bay as the address on a Christmas card. And, yes, it still got to me.

‘So, where are they?’ I asked.

‘Word is that they’ve upped sticks in North America and moved to the Gold Coast. Are you interested?’

‘Are they dangerous?’

‘Yes. Are you interested?’

‘How dangerous?’

The seconds ticked by while I waited for Brian to reprimand me for answering a question with another question. Instead, he surprised me by uttering a sigh and saying, ‘Scout, all cults are dangerous to someone.’

Ignoring his patronising tone, I asked, ‘How good’s the source?’ If the information wasn’t reliable there would be no story, and I could waste several days doing research for which I wouldn’t be paid.

‘I’ll be honest with you, Scout, it’s not the best, but instinct tells me this lead’s good. Someone in upstate New York was concerned enough by the cult’s activities to send a warning letter three months ago to a Sydney newspaper. The paper didn’t publish it, as the letter was anonymous. A colleague sent it on to me yesterday. Look, are you interested or are we going to play this game for a while?’

‘Read the letter to me, please, Brian.’

‘I’ll send it to you if you’ll do the story.’

We’d reached catch 22. Brian wouldn’t allow me to be privy to the contents of the letter until I agreed to do the story. I could see his point, but it meant making a decision without the facts.

‘Why me?’ I ventured, unsure if I was playing for time to weigh my options or enjoying pushing Brian to the edge of his endurance. Both, I suspect.

‘You’re the only journo I know who won’t let personal opinion influence the story.’

It was a feeble attempt at flattery, but it still gave me a buzz. Brian’s aware of my fascination for the dark side of the human psyche, and anything that hints at the abuse of power by an authority figure is right up my alley. He would have known that my sleuth synapses were already firing.

‘What sort of . . . er . . . cult activities?’ I asked.

‘Kidnapping the nation’s youth and coercing them into dodgy derring-do.’

‘It sounds like something out of Oliver Twist.’

‘Last chance,’ Brian said.

My heart rate had already gone up a notch and I felt the thrill of the chase. The article I was about to write on TV marketing of internet dating services would pay well, but the subject bored me to distraction and could wait. Plus, there was enough money in my bank account to last two months. I made a snap decision.

‘I’m on it,’ I told him.

‘Good girl, this is mainstream interest,’ Brian assured me. ‘Readers suck up cult stories as easily as the lost are sucked into cults. Give me names, family separations, human tragedy and crime. Deviant sex would be good. You’ve got six weeks. Usual terms.’

Brian knew perfectly well his ‘good girl’ comment would hit the mark, just as he knew my work would reflect what I found, not what he requested. One of the things I love about freelance writing is that it allows me to retain professional integrity and not be influenced by an employer’s agenda. Unless I’m broke, and then I’d sell my soul to the devil.

Suppressing the desire to verbally box his ears, I thought it better to end on a high note.

‘Dodgy derring-do?’

‘Yes, well dodgy,’ Brian shot back, and then he hung up.

Chairman Meow, who was now awake and watching a moth fluttering on the windowpane, didn’t appear nearly as excited about this as me.

I threw up my hands.

‘What?’ I said to the cat. ‘What danger could there possibly be?’

Unfortunately, he didn’t answer.

After finalising the Newsweek article, I brewed a pot of Assam tea and deliberated on how to tackle this new project.

Normally, when starting an investigation, I adopt the ethical approach of declaring upfront my journalistic intent, but cults are unknown territory and this one certainly sounded dubious. It might be safer, I reasoned, to work undercover until I had a firm grasp on the lie of the land.

By the time the tea was poured, I had formulated the bare bones of a plan and couldn’t wait to get cracking. Some people smoke cigarettes to help them think. I brew tea.

The phone rang again the moment I sat at my desk. It was probably Brian calling to say he’d forgotten to mention that the cult were axe-wielding murderers. I picked up the receiver and was mildly relieved to hear Bodkin’s distinctive Yorkshire brogue.

‘Hi lass,’ he said. ‘Are we still on for Tuesday night?’

‘Yes, we’re meeting at midnight on my back verandah.’

‘I’m a bit nervous about this one,’ Bodkin admitted. ‘It’s a hazardous target, particularly for me. Are we sure all bases have been covered?’

‘We’ll run through everything again at the meeting,’ I reassured him, ‘and head out about 2 am.’

‘What’s the visibility?’

‘The target has bright lights but there’s no moon, which will help if we have to escape. If you want to pull out, it’s okay. Everyone will understand.’

‘Ah, lass, never let it be said that Bodkin piked on a mission. See you on Tuesday.’

Bodkin, as you might have guessed, is not his real name. He and I are fellow members of an intrepid band of five yarn bombers known as the Guerilla Knitters Institute. GKI for short, we venture out in the dead of night and secretly decorate a variety of public objects—statues, trees, signposts and lampposts—with articles made from good old-fashioned wool. And if you were thinking this sounds like a form of graffiti, you’d be absolutely right, although we prefer to view our artistic creations as urban beautification.

Why do we do it? The bottom line is that yarn bombing is a covert adrenaline rush that’s tremendous fun. Although it’s against the law, we never do any permanent damage and our creative and quirky endeavours are almost always met with amusement and delight.

GKI started out small by knitting colourful flowers and attaching them to bushes and public benches in town, then we graduated to crocheting spiders’ webs in silver thread and tying them in trees in the park. Whilst this was fun, it wasn’t really risky and didn’t have the sense of purpose or meaning that we craved. It wasn’t until Bastille Day a few years ago that we realised the meaningful possibilities of our public art creations.

We had dressed toy koalas in knitted black berets and blue and white striped sweaters and positioned them in trees near the beach. I can’t begin to tell you the pleasure it was to witness the joy on people’s faces as they pointed up at the French koalas. It still brings a smile to my face every time I think of it. The stunt attracted brilliant media coverage and a local radio station sold off the koalas and donated the money to a youth group. I bought one myself and it sits on a chair in the corner of my bedroom. Its name is Charles de Gaulle (the koala, not the chair).

After that there was no stopping GKI, and our missions have been as wild, imaginative, funny and risky as the oddball minds that inspired them. Naturally, owing to the covert nature of our activities, we never use our real names on the phone, at meetings or on missions. Instead, we each have our own tag-name. For those not familiar with the word ‘bodkin’, it’s a large-eyed, blunt needle-like instrument used for threading cords or ribbons through knitted objects. Bodkin can never remember anyone else’s tag so he refers to us all as ‘lass’.

Needles had created our next mission and, as always, she had come up with something that was potentially hazardous but very funny. Bodkin had more to risk on this one than the rest of us, but to date he’s never let his professional standing as a senior partner in a well-known law firm interfere with GKI activities. I could see, though, how this one could be difficult for him if we were caught.

Chapter 2

The Gold Coast is only an hour’s drive north of Byron Bay, just over the State border in Queensland, so I could work from home on the cult story—home being my comfortable old apartment above Fandango’s restaurant. The upside is that I can wear a swimsuit and sarong to work. The downside is my tendency to be distracted by domestic chores, morning naps with a good book, afternoon naps with a good book and the view from the study window.

My desk overlooks Byron’s main thoroughfare, Jonson Street, where the muse in charge of fabulous things has dropped the biggest fancy-dress party in the world. Everyone’s there—ladies who lunch, Armani-clad executives, tattooed trendies, hemp-wearing greenies, suntanned backpackers and new-age hippies. And I mustn’t forget old Mrs Delgado in a psychedelic kaftan, dragging along her tartan trolley and shading herself from the sun under the town’s largest rainbow-inspired golf umbrella. If a strong wind ever blew down Jonson Street, Mrs D would be in New Zealand.

Toby tells me that I spend too much time watching this galaxy of exotic humanity, but he’s wrong, as usual. Mostly I daydream about totally unsuitable scenarios involving the handsome men that saunter past.

Catching the fast train back to reality, I emailed Brian, thanked him for the commission and reminded him to scan me the letter from New York and, if he had it, the postmark on the envelope. My spirits plummeted when Brian’s out-of-office reply popped into my inbox advising that he wouldn’t be back at work until Monday. Hmmm? As well as possessing appalling manners, Brian could also be extremely devious. It was entirely possible that there was something in the letter he didn’t want me to see.

Great! Now I was flying blind on this thing.

Chairman Meow watched with interest as I took my annoyance out on the study whiteboard and furiously cleaned off notations from the Newsweek job. I use the board as a visual mind map for recording everything relating to a case, whether it appears relevant at the time or not. As well as providing a record of progress, it occasionally acts as a catalyst, exposing links Dick Tracy here might otherwise not have seen.

‘There,’ I said to Chairman Meow, ‘it’s never been so clean.’ He looked at the whiteboard cloth and, perhaps assuming that he might be in for a bit of the same treatment, jumped off the chair and darted out of the study.

‘Mad cat,’ I muttered as I drew a wide rectangular box in the centre of the whiteboard and wrote The Luminous Renaissance of Illustrious Light inside the box. I stood back to admire my handiwork, and savoured the excitement that comes with the dawn of a new case. Despite my years of experience, the first words on the board are always a thrill.

Newspaper ads are also part of my usual MO when starting an investigation as they often elicit a lead or an angle. The ad I drafted was simple and to the point—Anyone with a friend or family member who has joined the Luminous Renaissance of Illustrious Light, or has any information about this organisation, please call the following number . . .

I placed my mobile phone number in the ad but didn’t include my name or profession, or the reason I wanted the information. The prospect of some crazy cult member tracking me down and firebombing my home was already lurking at the back of my mind.

Satisfied with the wording, I called the classifieds and placed advertisements to run for seven days, starting the following day, in the Gold Coast Bulletin and the Brisbane Courier Mail, and another to run next week in the weekly Byron Shire Echo.

At lunchtime I cobbled together a cheese sandwich and switched on the TV to catch the news. Last year, when Toby was reporting for CNN, I often saw him on television standing in a bombed-out street looking brave and handsome in a helmet and camouflage gear. These days he doesn’t file live reports, but I still tune in to make sure no Australian journalists have been killed in the line of duty.

For the most part I’m pragmatic about Toby’s dangerous occupatio

n, although I’ve had the occasional meltdown. A month ago, in a rare display of public emotion at Coolangatta Airport, I clung to Toby until he eventually broke away from me and passed quickly through security. It was dramatic, like a scene from Casablanca. I blubbered in the car all the way back to Byron Bay—well, at least as far as the car park exit, but I emailed Toby and told him it was all the way home.

The news over, I returned to my desk.

Initial internet searches revealed two things about the Luminous Renaissance of Illustrious Light: firstly, there was hardly any data from legitimate research; and secondly, the name was a dyslexic’s nightmare to type into search engines.

There was a brief moment of joy when I found a website which advised that the cult was based near Saratoga Springs, in the foothills of the Adirondack Mountains of upstate New York. Unfortunately, there was no mention of the Gold Coast or Australia, which made me wonder how reliable Brian’s information was.

I’ve hiked in the Adirondacks—although technically I suppose it was walking from the car to a picnic table, but what’s important here is my familiarity with the area. The Adirondack Mountains are six million acres of stunning wilderness, nirvana for groups of secretive souls seeking utopian togetherness. It didn’t make sense to me that a cult would move from a remote location, where they could safely exert ideological control over their followers, to the glitz and glamour and chaotic subtropical delights of Australia’s Gold Coast.

The realisation hit me broadside. As always, I was forgetting the Gold Coast hinterland—the mountains and World Heritage rainforest, areas so remote that whole planes had been lost. Oh, all right, so it was only one plane, but you get the point. If the cult was on the Gold Coast, its most likely location would be the hinterland.

On the whiteboard I drew a satellite line outwards from the central box and at the end of the line made a smaller box in which I wrote Anonymous letter from NY. Then I drew another line and box for Adirondacks and Saratoga Springs.

I felt a sudden stab of sadness at the memory of visiting Saratoga with Toby in the summer of 2007. Ostensibly we’d gone to see Dan, Toby’s doctor cousin, and to make our fortune at the famous Saratoga races, only it didn’t quite work out that way. Owing to Toby’s obsession with war we spent an inordinate amount of time at historic battle sites, and then proceeded to turn them into modern-day battle sites. It wasn’t the happiest of holidays.

Mad Men, Bad Girls

Mad Men, Bad Girls Good News, Bad News

Good News, Bad News